Why Canada Is Paying the Highest Price in Venezuela’s Collapse

Trump’s oil gamble, Canada’s crisis.

Less than a week into 2026, President Donald Trump made his boldest move yet in reshaping North American energy markets. On January 3rd, in a military operation that stunned international observers, U.S. forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores, flying them to New York to face federal charges related to drug trafficking and alleged collaboration with designated terrorist organizations.

For Canadians watching from the sidelines, the spectacle might have seemed distant—just another chapter in Washington’s long history of interventions in Latin America. But beneath the geopolitical drama lies a more immediate concern: Trump’s explicit intention to seize control of Venezuela’s vast oil reserves could fundamentally reshape the global heavy crude market that Canadian producers have come to dominate.

“We’re going to have our very large U.S. oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure, the oil infrastructure, and start making money for the country,” Trump declared hours after the operation. The message was unmistakable—this wasn’t about democracy or drugs. It was about oil.

Canada’s Precarious Position

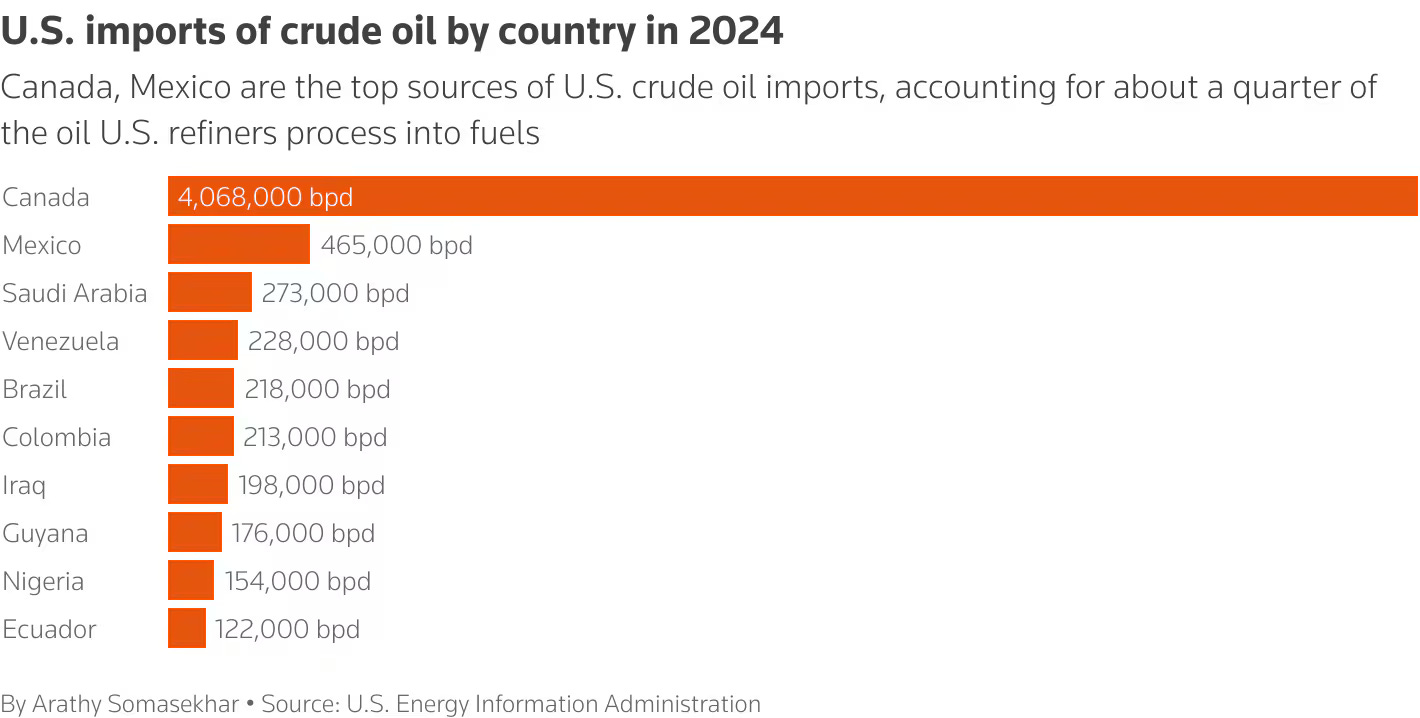

Canada has spent the past two decades building an energy relationship with the United States that now underpins much of its economic prosperity. In 2024, Canadian crude oil exports averaged 4.20 million barrels per day, with 3.33 million barrels (79%) consisting of heavy oil. The value of U.S.-Canada energy trade reached $151 billion in 2024, with $124 billion representing U.S. energy imports from Canada.

These aren’t just numbers on a spreadsheet. They represent the economic lifeblood of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and by extension, the entire Canadian federation. Alberta’s oil and gas industry accounted for roughly $88 billion of GDP in 2024, equivalent to 25% of the province’s economy. More than 200,000 Albertans work directly in the sector, with an estimated 500,000 jobs when indirect employment is included.

The vulnerability is stark: over 95% of Canadian crude oil exports went to the United States in 2024. Canada has, in effect, placed nearly all its energy eggs in one basket, a basket now controlled by an administration eyeing alternative sources of the same product Canada sells.

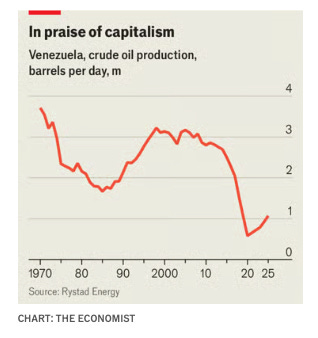

To understand the threat, one must appreciate what Venezuela represents. The South American nation possesses the world’s largest proven oil reserves, 303 billion barrels, dwarfing Saudi Arabia’s 267 billion and Canada’s 168 billion. Venezuela is a founding member of OPEC and was once a global energy powerhouse, producing more than 3 million barrels per day in the early 2000s.

But decades of mismanagement, corruption, and economic decline have left its infrastructure in ruins. Venezuela today produces only about 950,000 barrels per day, less than 1% of global oil output. By comparison, the United States produces about 13.5 million barrels daily, while Canada produces approximately 5 million.

The country’s oil history reads like a cautionary tale of resource curse. After foreign companies like Shell and Standard Oil made Venezuela the world’s top oil exporter by 1928, the government nationalized the industry in 1976, creating Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA). What followed was a slow-motion collapse, a nation sitting atop unimaginable wealth, yet unable to extract it.

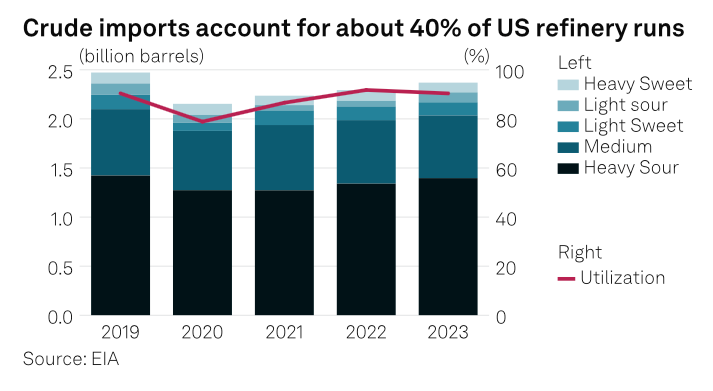

Canada's vulnerability is particularly acute because of the type of oil it produces. The crude extracted from Alberta's oil sands is heavy and dense, requiring specialized refining capabilities. This places Canadian oil in the same category as Venezuelan crude, what the industry refers to as heavy oil, notable for its high carbon intensity and the complex processes needed to extract and refine it.

Much of Venezuela’s oil historically went to refineries along the U.S. Gulf Coast in Texas and Louisiana, facilities specifically designed to process heavy crude. When U.S. sanctions effectively shut down Venezuelan exports over the past decade, Canadian producers filled the void. Canada now supplies approximately 60% of all U.S. crude imports, roughly nine times more than the next biggest supplier, Mexico.

The majority of U.S. crude imports now consists of heavy oil, rising from just 12% in 1970 to 70% in 2024. This dramatic shift has been driven almost entirely by Canadian supply, as Venezuela’s contribution has collapsed to nearly nothing. Canadian heavy crude imports to the U.S. surged from 15% of all U.S. imports to 61% over recent decades.

If Venezuela’s production rebounds under U.S. influence, Canada’s leading market share suddenly looks far less secure.

The implications for Canadian producers are sobering. Between 2017 and 2019, the average break-even price for oil sands production was $51.80 per barrel. While cost reductions have lowered this by $10-$15 per barrel, many projects still operate on thin margins. If global oil prices fall below $50 per barrel due to increased Venezuelan supply, a real possibility in an already oversupplied market, many Canadian operations could become unprofitable.

The job losses would be immediate and severe. Alberta’s oil and gas sector has already experienced significant contraction, declining from 171,000 jobs in 2015 to 150,200 by 2024. Imperial Oil announced plans in late 2025 to cut 20% of its workforce. ConocoPhillips has signaled further reductions due to falling oil prices and global oversupply.

The ripple effects would extend far beyond the energy sector itself. For every dollar drop in oil prices, Alberta’s provincial revenues lose approximately $750 million, money that funds schools, hospitals, and public services. Construction, manufacturing, and professional services that depend on energy sector spending would feel the squeeze immediately.

Trump’s Reality Check

Before Canadians panic, however, it’s worth examining whether Venezuela can actually deliver on Trump’s ambitious vision. The obstacles are formidable.

The Economist estimates that returning Venezuelan production to levels from 15 years ago would require $110 billion in capital expenditure on exploration and production. Bloomberg reports that major oil companies remain deeply skeptical about pouring substantial sums into a country run temporarily by a U.S.-backed government without established legal and fiscal frameworks. ConocoPhillips, still owed over $10 billion from international arbitration against Venezuela, said it was “premature to speculate on any future business activities or investment.”

Bob McNally, president of Rapidan Energy Group, notes that “just stabilizing existing production will require low single-digit billions of dollars for workovers, power, water handling and export infrastructure repairs.” As Bloomberg puts it: “Nearly every major company has been beguiled by the underground riches of Venezuela. Over the past century, they have discovered that there was a lot of money to be made, but also a lot to lose.”

Beyond capital, Venezuela faces a severe brain drain. Tens of thousands of skilled workers have fled the country over the past decade. Rebuilding PDVSA’s technical capacity to form viable joint ventures with Western firms may prove more difficult than simply fixing physical infrastructure.

Then there’s the market itself. The International Energy Agency expects global crude supply to outstrip demand until at least the end of the decade because of strong production, particularly from U.S. shale operations and OPEC nations. Adding millions of barrels of Venezuelan crude to an already saturated market could depress prices for everyone.

Most analysts believe any significant increase in Venezuelan production is a decade away, not a year or two. Francisco Monaldi, director of the Latin America energy program at Rice University, predicted it would take at least a decade, and investments of more than $100 billion, to rebuild Venezuela’s oil infrastructure and lift production to 4 million barrels per day.

Canada’s Strategic Response

Still, even if the Venezuelan threat proves more theoretical than immediate, Canada cannot afford complacency. The episode underscores the fundamental vulnerability of the Canadian economic model: extraordinary dependence on a single customer for its most valuable export.

The completion of the Trans Mountain Expansion pipeline in 2024 was supposed to address this vulnerability by opening access to Asian markets. Exports of crude oil to countries other than the United States rose 59.8% to an annual record of 10.6 million cubic metres in 2024. This is progress, but it barely scratches the surface, non-U.S. exports still represent less than 5% of Canada’s total crude oil shipments.

The deeper challenge lies in Canada’s overall economic structure. The country has built an enviable position as a stable, reliable supplier of resources to the world’s largest economy. But that position comes with inherent fragility when the buyer’s interests shift or when cheaper alternatives emerge.

Diversification has been the rallying cry for decades, yet progress remains glacial. While the United States has built a dynamic technology sector that now rivals traditional manufacturing as an economic engine, Canada continues to derive a disproportionate share of its prosperity from extracting and selling raw materials. This made sense when commodities were scarce and prices high, but in an era of climate transition, geopolitical volatility, and Trump-style protectionism, the strategy looks increasingly risky.

Looking Ahead

The Venezuelan situation may ultimately amount to little in practical terms. The country could remain mired in chaos for years, with production recovering only marginally. Global oil markets may remain oversupplied regardless of what happens in Caracas. Canadian oil may continue flowing south for decades to come, with prices remaining stable enough to keep operations profitable.

But the episode serves as a warning shot. Canada’s economic model, heavily dependent on resource extraction, overwhelmingly oriented toward a single customer, vulnerable to both price swings and political shifts in Washington, looks less sustainable with each passing year.

The path forward requires difficult choices. Canada must continue pushing to diversify export markets, even as it acknowledges this is a decades-long project given infrastructure requirements and geographic realities. It must invest more aggressively in value-added processing to capture more economic benefit from resources before they leave the country. And most fundamentally, it must build economic strengths beyond the energy sector, in technology, advanced manufacturing, services, that can sustain prosperity if and when the oil market shifts.

This isn’t about abandoning the energy sector, which will remain vital to Canadian prosperity for years to come. It’s about recognizing that a nation cannot build long-term security on the foundation of a single commodity sold to a single buyer. Trump’s Venezuelan gambit may or may not succeed, but the message it sends is unmistakable: in the new era of American energy policy, Canada’s privileged position is no longer guaranteed.

For now, Canadians can only watch and wait, hoping that Venezuela’s oil remains buried deep underground, at least for a little while longer.