Canada's 2026 Economic Outlook

Key trends shaping economic growth, employment, and trade

If there’s anything you remember about the economy in 2025, it’s probably one of these: Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs in April that sent markets tumbling, wages that still can’t keep pace with grocery bills, or if you’re fresh out of school, a job market that felt like pushing against a locked door.

One word to sum it all up? Uncertainty.

On paper, last year was supposed to break Canada’s economy. Trade tensions with the United States pushed the economy into contraction by summer. Unemployment climbed to 7.1%. According to Bloomberg News, consumer confidence collapsed in November, with 45% of Canadians expecting things to get worse and only 20% seeing any light ahead.

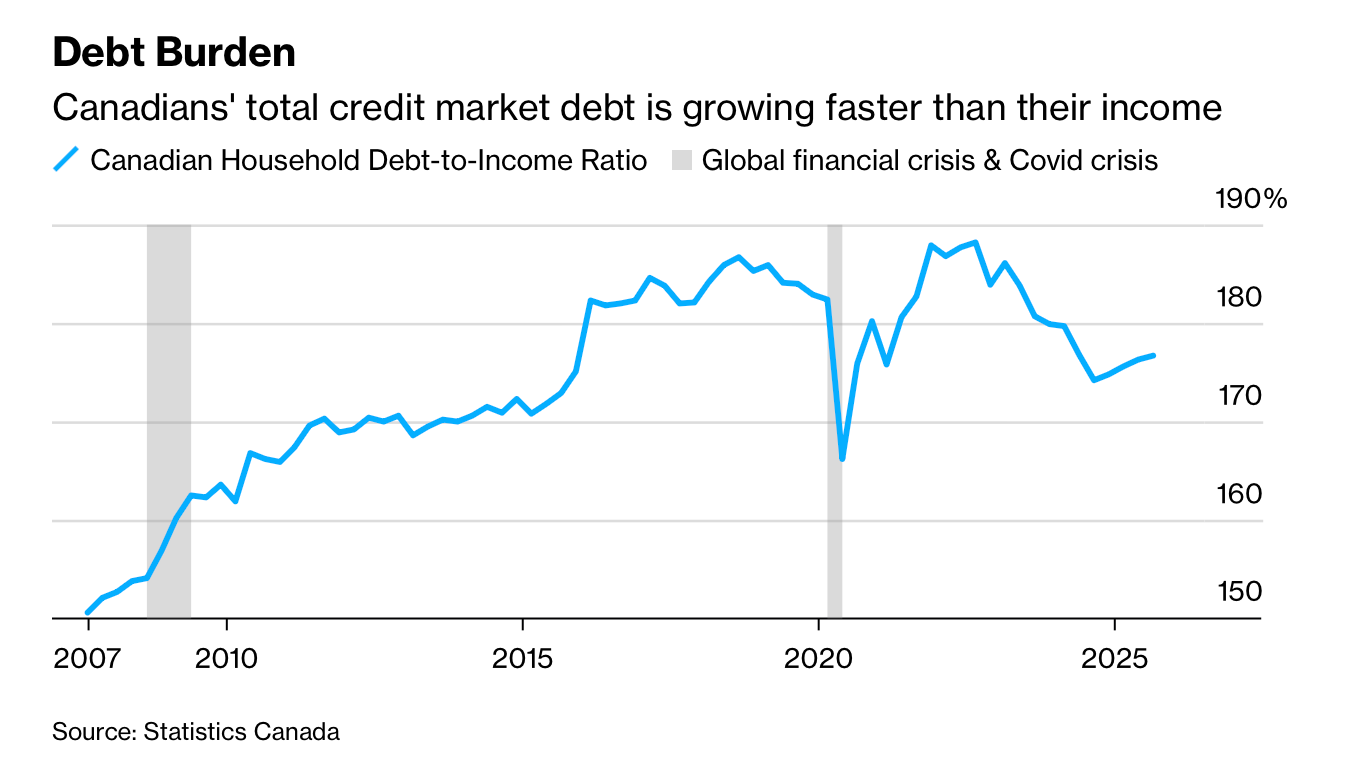

Yet somehow, Canada’s economy hung on. Canadians kept spending, especially during the holiday season. Retail sales jumped 1.2% in November. The S&P/TSX stock index surged 28% for the year. Mortgage payments kept getting made. By year’s end, unemployment had dipped back to 6.5%.

It was one of 2025’s most perplexing contradictions: an economy that looked broken on paper but kept moving forward anyway. That same tension is now shaping 2026.

Here are the key themes defining Canada’s economy in 2026.

A Country Shrinking for the First Time

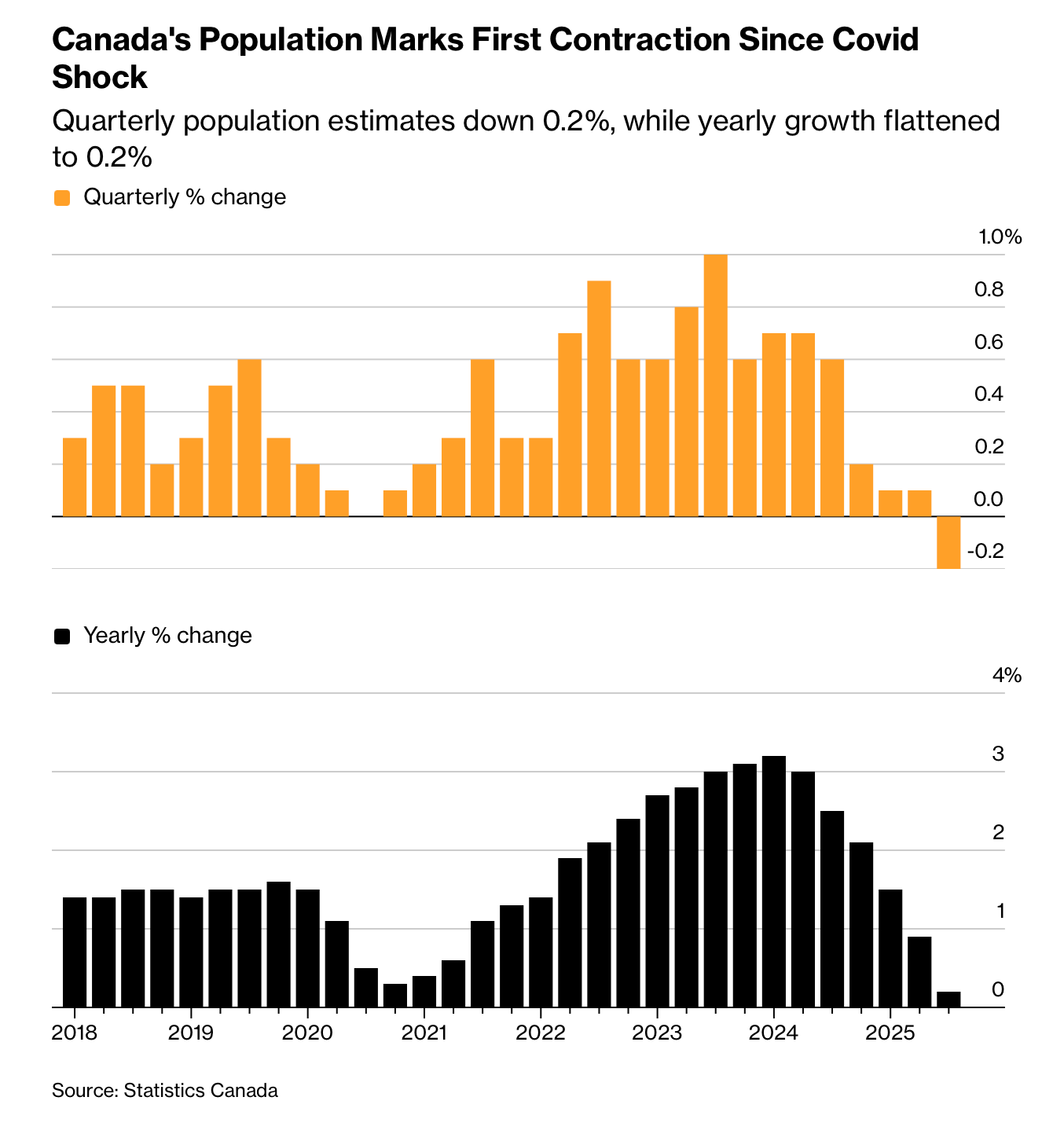

Canada’s population declined 0.2% in the third quarter of last year, dropping to 41.6 million people. This marks the first such decrease in recent memory for a country that built its modern identity on immigration and population growth. The decline isn’t primarily about birth rates, though Canada’s fertility rate has fallen below 1.3 children per woman. It’s about a dramatic reversal in immigration policy.

The Trudeau government’s decision to allow Canadian colleges to recruit massive numbers of international students, largely from India, created severe strain. Housing and public services couldn’t absorb the influx. Public opinion shifted, policy changed, and non-permanent residents began leaving. The engine that powered Canada’s growth for decades is now running in reverse, and the Bank of Canada expects this trend of slower population growth to persist in 2026.

The Fragile Trade Relationship

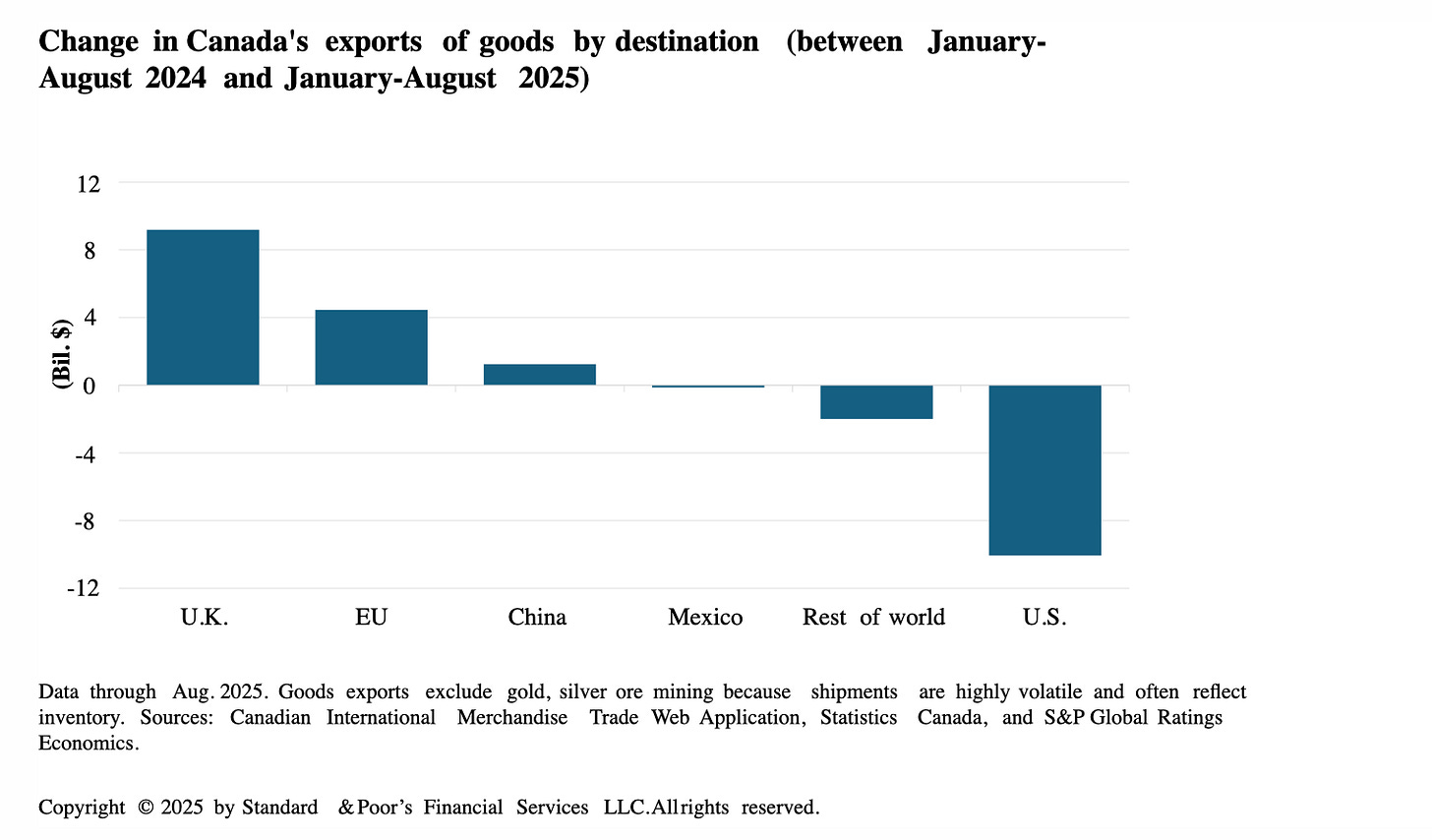

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), previously called North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), renewal in 2026 was meant to be routine. It increasingly looks like a renegotiation. While most Canadian exports to the United States, 86% as of September, remain duty-free, the tariffs that were imposed targeted Canada’s industrial core: automotive, steel, lumber. Workers in manufacturing and resource extraction, particularly young men in labor-intensive sectors, absorbed the impact.

The uncertainty isn’t just economic. It’s existential. Canada sends roughly three-quarters of its exports to the United States. When that relationship becomes unstable, the entire Canadian economy holds its breath.

The Consensus Forecast: Modest Growth, High Uncertainty

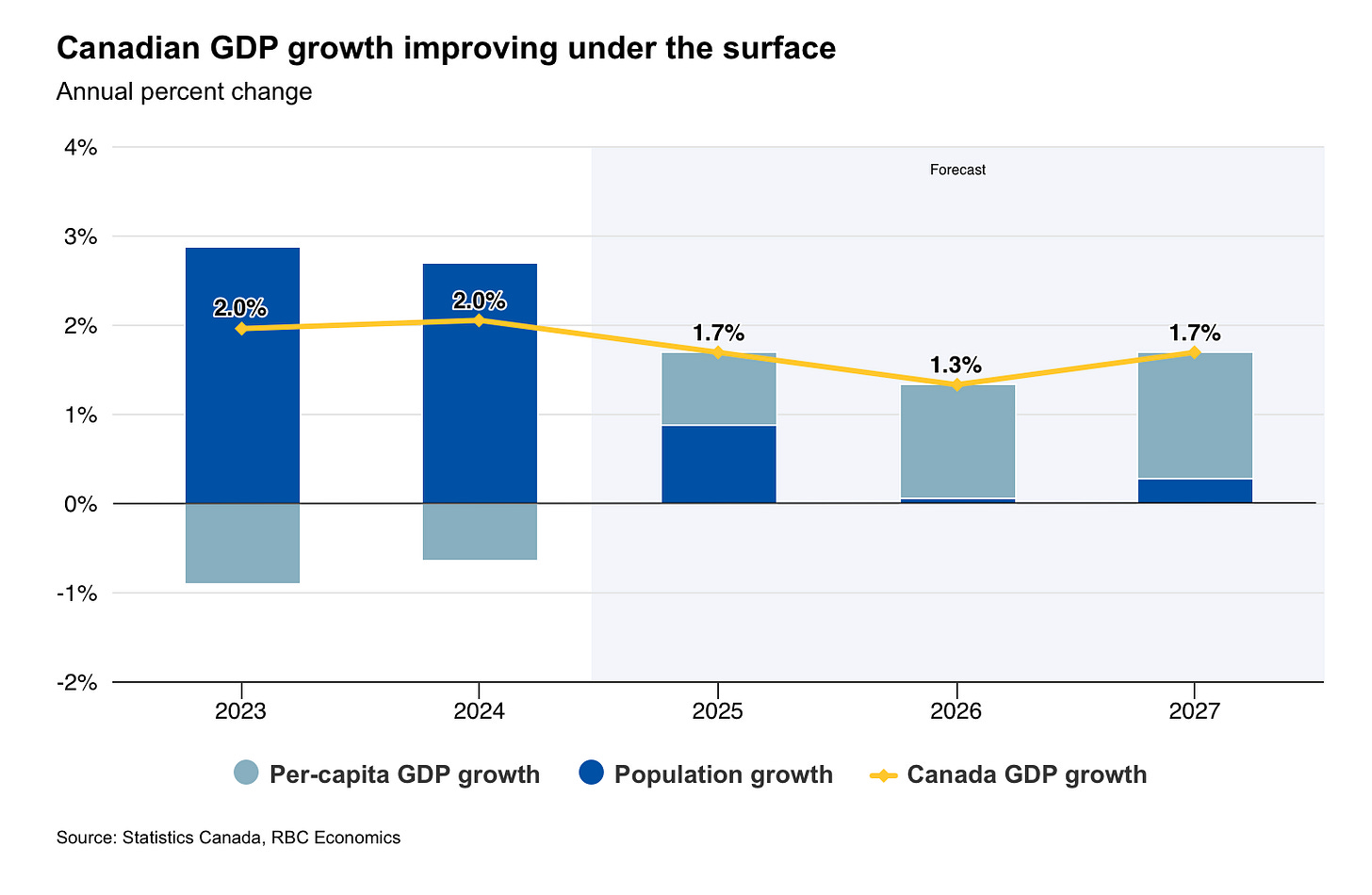

Major forecasters—RBC, TD, BMO, Desjardins, S&P Global—paint a similar picture for 2026: growth around 1% to 1.5%, inflation holding at 2%, and cautious optimism that the worst has passed. Interest rates have stopped falling. The Bank of Canada cut rates aggressively from 5% to 2.25% between June 2024 and late 2025, then signaled it was done.

Fiscal spending is ramping up dramatically. The federal deficit is doubling from an initial $40 billion estimate to $80 billion, representing about 2.5% of GDP. Much of this spending targets defense, infrastructure, and support for businesses affected by tariffs. This is traditional Keynesian stimulus, government spending to sustain demand when private sector confidence wavers.

Global commodity prices are holding up, which matters enormously for a resource-dependent economy like Canada. When oil, gas, lumber, and minerals fetch decent prices internationally, money flows through Alberta, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia, eventually reaching the rest of the country. And critically, the U.S. economy, while soft, isn’t collapsing. A weak American economy would devastate Canada. A moderately growing one provides sufficient demand to keep Canadian exporters in business.

The Housing Market Remains Problematic

Economist Benjamin Tal of CIBC Capital Markets framed it perfectly: homes are “too expensive to buy, [but] not expensive enough to build.” The market is frozen. Ontario and British Columbia are experiencing a housing recession, with Toronto condo prices down 22% from their peak. Tal expects another 10% to 15% decline before bottoming, with Vancouver showing similar patterns.

The fundamental problem is that construction has essentially stopped—”we are building basically zip now,” as Tal describes it—yet demand pressures remain intense despite immigration being dramatically curtailed. Years of elevated immigration created a massive backlog of unmet housing needs.

Tal points to “doubling up”—multiple families sharing single households due to unaffordability—which he estimates affects 30% of households in Toronto and Vancouver. “We are underestimating how difficult the situation is,” Tal explains, because these arrangements mask true demand. As prices fall and affordability improves slightly, “un-doubling” will unleash another wave of demand, compounding pressure from immigration (even at reduced levels) and young people forming new households.

For young potential buyers, this creates a difficult calculation. Falling prices appear opportune, but the correction reflects people being priced out rather than genuine affordability. Prices sit in a no man’s land: too low to stimulate construction, too high for most buyers to enter. Construction is slowly returning, but most economists suggest saving and waiting until 2027, when building activity should normalize and signal a healthier market. Until then, investment appetite remains weak, as uncertainty about trade, immigration, and government policy makes long-term capital commitments difficult.

Navigating Uncertainty

The word appearing most frequently in 2026 forecasts is “uncertainty.” Trade tensions with the United States, especially around the USMCA review. Immigration policy shifts. The interaction between slower population growth and labor shortages. Global commodity price swings. Federal deficit spending and its long-term implications.

Economists expect GDP growth of 1% to 1.5%, below trend but not recessionary. They expect inflation at 2%, wage growth at 3%, gradually declining unemployment, and stable interest rates. These are reasonable baseline assumptions, but the confidence intervals around them are wider than usual. Small changes in U.S. trade policy, immigration rules, or global economic conditions could push Canada significantly above or below that baseline.

The Canadian economy in 2026 resembles a ship navigating through fog. The vessel itself is sound, resources, an educated workforce, proximity to the U.S. market, political stability. But visibility is poor. The Bank of Canada and federal government are being cautious, holding rates steady while spending to maintain momentum. For those aboard, the sensible approach is straightforward: maintain your balance, watch your footing, avoid sudden movements. The fog will eventually clear. Until then, careful optimism is warranted, but not complacency.