Why Canadian Home Prices Keep Rising

Why falling prices won't restore affordability

If you’ve ever looked at home prices in Vancouver or Toronto, you’ve probably wondered: why do they keep climbing, even when everyone agrees housing is unaffordable? The answer lies in a concept from economics called elasticity, and understanding it explains why Canada’s housing crisis is so stubborn, and why some cities suffer far more than others.

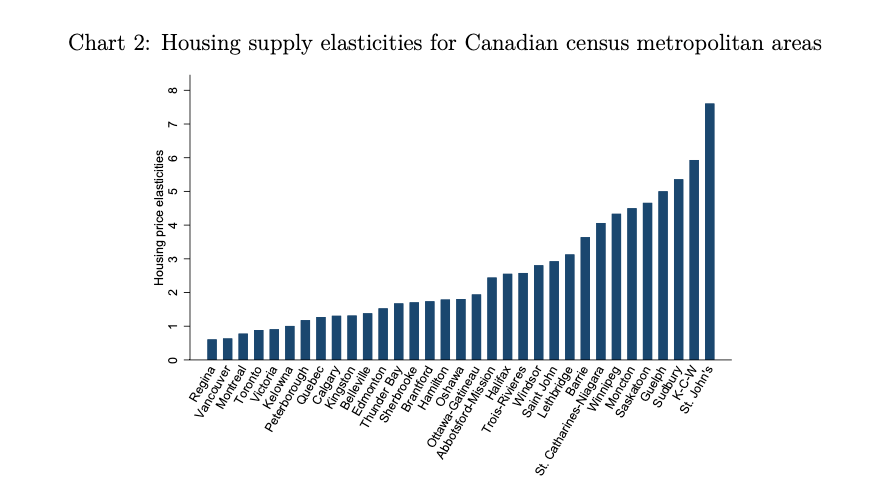

Consider this: Vancouver and Winnipeg both experience a 1% increase in housing demand, maybe from population growth, lower interest rates, or investor activity. In Winnipeg, home prices rise by just 0.23%. In Vancouver, they jump by 1.57%, nearly seven times more. Same demand shock. Wildly different price outcomes.

The answer is housing supply elasticity. Think of elasticity like a pressure valve. When demand increases, elastic supply acts like an open valve, builders quickly construct new homes, releasing the pressure before prices skyrocket. Inelastic supply is like a stuck valve, pressure has nowhere to go but into higher prices.

Winnipeg has highly elastic supply, with an elasticity measure of 4.43, meaning builders can rapidly respond to demand by constructing new homes. Vancouver’s supply is highly inelastic at 0.63, meaning construction can’t keep pace no matter how high prices climb. The result? Vancouver homebuyers absorb the demand shock almost entirely through higher prices, while Winnipeg absorbs it through more housing. This single difference in elasticity explains much of why Canadian housing has become a crisis in some cities but not others.

Housing supply elasticity measures how much new construction responds to price increases. An elasticity above 1 means supply is elastic—a 1% price increase generates more than 1% increase in new homes. Below 1 means supply is inelastic—prices can double while new construction barely budges. The Bank of Canada estimates that the median Canadian city has a housing supply elasticity of 2.2, which is moderately elastic.1 But Canada’s largest cities—where most Canadians actually want to live—cluster far below this median. Toronto sits at 0.64, and Montreal also falls below 1. These figures are similar to constrained American cities like New York at 0.63 and San Francisco at 0.72.

Several factors conspire to make supply inelastic in Canada’s major urban centers. Vancouver is bounded by ocean, mountains, and the U.S. border. Toronto faces similar constraints with Lake Ontario and the Greenbelt. Unlike Winnipeg or Calgary, these cities can’t simply expand outward indefinitely. Limited land means limited ability to respond to demand with new supply.

But geography isn’t destiny. Most residential land in Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal is zoned exclusively for single-family homes, prohibiting medium-density housing like townhomes or low-rise apartments. This “missing middle” housing could absorb demand, but zoning makes it illegal to build. When 70-80% of residential land allows only the lowest-density housing, supply becomes inherently inelastic. Even when housing is approved, builders face lengthy approval processes and substantial upfront costs. Vancouver has an estimated 100,000 approved homes stalled due to high development charges and financing costs. These barriers mean that even when prices signal strong demand, supply can’t respond quickly, the hallmark of inelasticity.

Construction itself presents constraints. Building housing requires labor, materials, and expertise. During boom periods, shortages in skilled trades, supply chain bottlenecks, and limited development capacity all contribute to inelastic supply. Unlike manufacturing, you can’t simply double housing production overnight.

Understanding elasticity transforms how we interpret Canada’s housing market trends over the past two decades. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, home prices across Canada typically hovered at 3-4 times annual provincial income. By 2022, this ratio had surged to 16 times income in major urban areas. To put that in perspective, if you make $60,000 a year, a home that used to cost about $240,000 now costs $960,000. That’s like having to work 16 years just to earn enough to buy a house, without spending a single dollar on anything else.

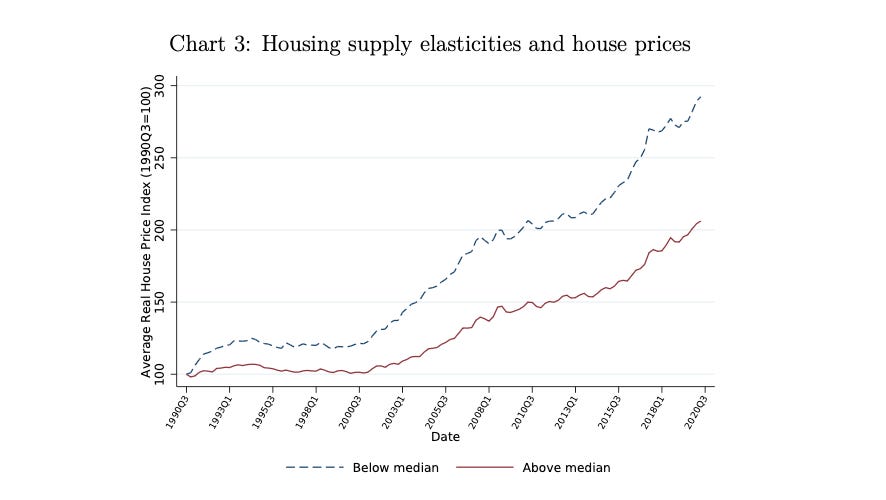

As demand increased—driven by immigration, low interest rates, and housing financialization—elastic cities like Winnipeg responded with more housing, keeping price-to-income ratios stable. Inelastic cities like Vancouver and Toronto couldn’t respond with supply, so all that increased demand translated directly into higher prices. Over time, this compounding effect created the massive price-to-income divergence we see today.

Between 1990 and 2020, Canadian cities with inelastic housing supply saw average home prices quadruple. Cities with elastic supply saw prices only triple. While a 4x increase sounds marginally worse than 3x, this compounds over 30 years. In an inelastic city, a $200,000 home becomes $800,000. In an elastic city, it becomes $600,000—a $200,000 difference in absolute terms. The elasticity gap explains why Vancouver and Toronto have become synonymous with housing unaffordability while cities like Edmonton and Saskatoon remain relatively accessible.

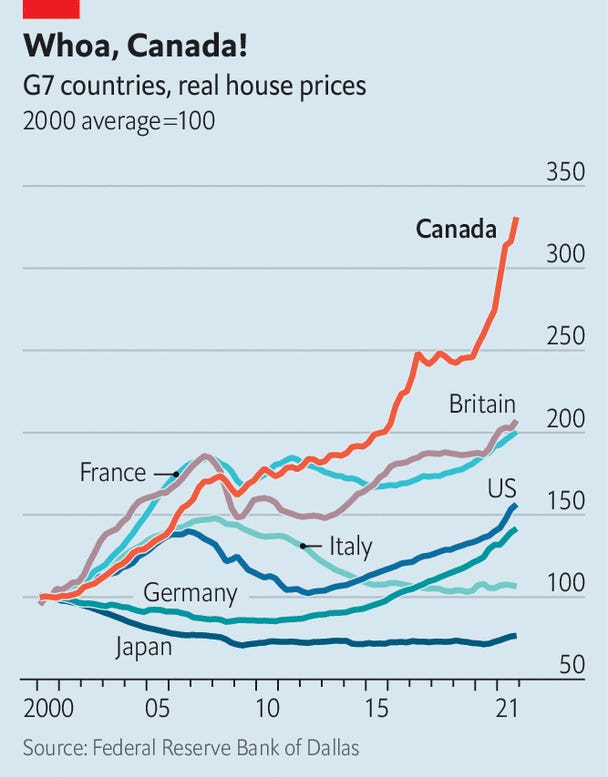

The elasticity framework also reveals why Canada and the United States diverged so dramatically after the 2008 financial crisis. During that crisis, American home prices fell 30% nationally, with some cities experiencing even steeper declines. Canadian prices dipped just 9% on average before resuming their climb. Since 2000, Canadian home prices have tripled while U.S. prices have risen only 60%.

The U.S. housing boom of the 2000s occurred partly in elastic sunbelt cities like Phoenix, Las Vegas, and inland California, where builders had massively overbuilt in response to speculation. When demand crashed, inelastic coastal cities saw sharp price drops, but elastic cities saw catastrophic collapses as excess supply flooded the market. Canada’s boom concentrated in inelastic cities like Vancouver and Toronto where overbuilding was structurally impossible. When demand softened slightly in 2008, there was no supply overhang to create a cascading price collapse. Inelastic supply protected Canada from a U.S.-style crash—but also prevented the affordability reset that American cities experienced.

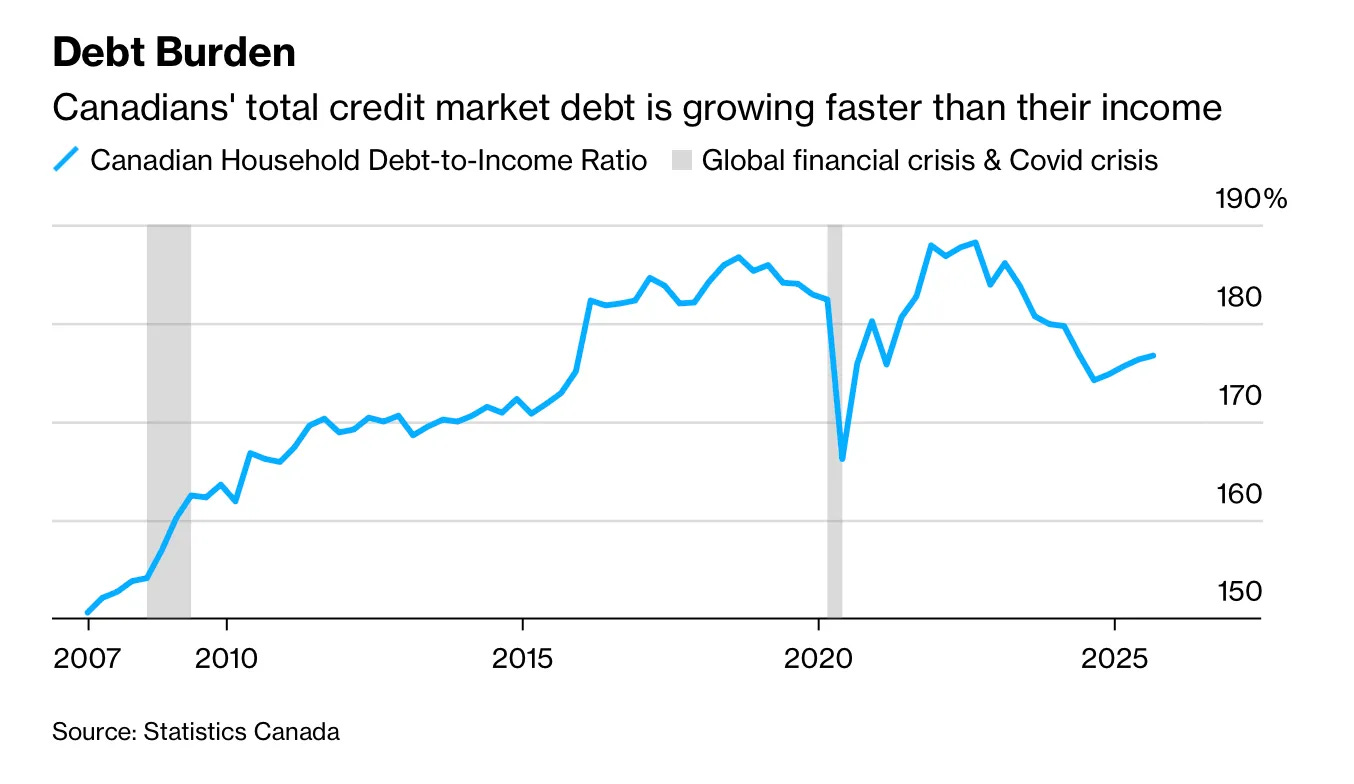

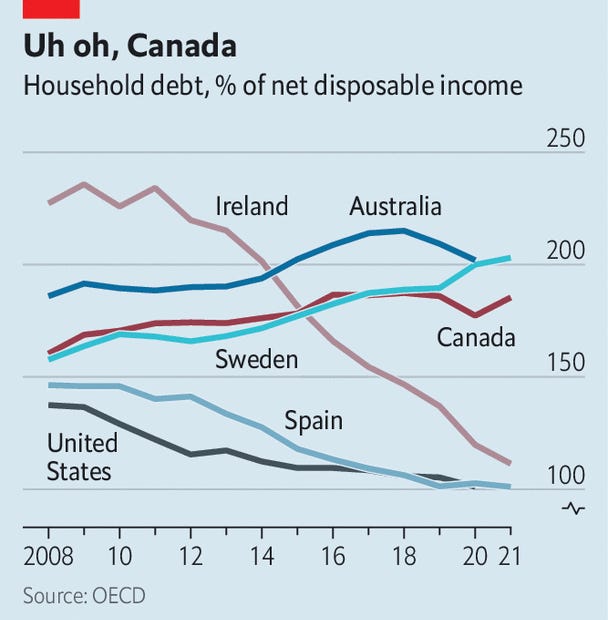

The consequences of inelastic supply extend beyond prices to household balance sheets. Canadian households now owe roughly $1.75-$1.80 for every dollar of disposable income—the highest in the G7 by a significant margin. Household debt represents 98-100% of Canada’s entire GDP, compared to about 75% in the U.S. and lower levels in other G7 nations.

Elasticity directly drives this debt burden. In elastic markets, when prices rise, supply responds and prices stabilize—potential buyers don’t need to take on extreme debt loads. In inelastic markets, buyers face a choice: accept being priced out, or stretch their finances to the breaking point. With supply unable to respond to demand, each cohort of buyers must bid against each other with increasingly leveraged offers. The result is a nation where homeownership increasingly requires taking on debt levels that would have been considered reckless in previous generations.

It’s tempting to blame Canada’s housing crisis entirely on demand-side factors: immigration, low interest rates, investor activity, or foreign buyers. And these factors certainly matter. Canada’s population grew by a record 1.2 million in a single year recently, driven primarily by immigration. This created acute pressure, pushing rental vacancy rates to a record low of 1.5% in 2023. One in five properties in Canada is owned by investors, with the figure reaching 41% and 36% respectively in Ontario and British Columbia condominiums. These investors treat housing as an asset class, creating additional demand that competes with primary residence buyers.

But elasticity reveals why the same demand pressures create crises in some cities but not others. Population growth creates housing demand everywhere. The question is whether supply can respond. Cities like Winnipeg and Calgary, with elastic supply, can absorb immigration with new construction. Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal cannot. The same immigration policy creates affordable housing markets in some cities and bidding wars in others, not because demand differs, but because supply elasticity differs.

In elastic markets, investor demand would trigger a construction boom, with builders racing to capture investment dollars by creating new supply. Prices would rise modestly, then stabilize as new supply comes online. In inelastic markets, investor demand simply bids up the price of the existing fixed stock. There’s no supply response to moderate prices—just more capital chasing the same limited inventory. Similarly, the shift toward a low interest rate environment since 2001 made borrowing cheaper, increasing what buyers could afford and boosting demand. But in elastic cities, cheap credit finances new construction, expanding supply. In inelastic cities, it finances bidding wars over existing homes.

The common thread: demand shocks—whether from immigration, investors, or interest rates—affect all cities. Elasticity determines whether those shocks resolve through more housing or higher prices.

In a typical market, when prices rise dramatically, we expect a self-correcting mechanism. High prices should incentivize producers to increase supply, which then moderates prices. The Bank of Canada’s modeling shows that a 1% increase in house prices in the median Canadian city is associated with a 2.2% increase in housing supply. This suggests the market does self-correct—when prices rise, builders respond.

But this median masks dramatic variation. In Vancouver, that same 1% price increase generates far less supply response because of the structural constraints: zoning, geography, regulatory barriers, and construction capacity limits. This means that in inelastic cities, the normal market mechanism is broken. Prices can rise 50%, 100%, even 200%, and supply still can’t catch up. Each price increase generates some supply response, but never enough to close the gap. The market remains perpetually out of equilibrium, with prices climbing ever higher while supply lags further behind.

Compare this to elastic cities where prices are more stable. When demand increases, builders can respond quickly and substantially. Prices might rise 10-15% to incentivize construction, builders flood the market with new homes, and prices stabilize or even decline slightly as supply catches up. The market self-corrects. Inelastic cities don’t self-correct—they spiral. And without addressing the underlying elasticity problem, no amount of waiting for “market forces” will restore affordability.

As of late 2025, Canada’s National Composite MLS Home Price Index has declined slightly, sitting 17% below its early 2022 peak. Some might see this as the beginning of a market correction that will restore affordability. Elasticity suggests otherwise.

A 17% decline from an inflated peak doesn’t restore affordability when prices were already severely elevated. More importantly, the structural factors creating inelastic supply haven’t changed. Zoning laws remain restrictive. Geographic constraints haven’t disappeared. Regulatory barriers still exist. Construction capacity remains limited.

What elasticity tells us is that without addressing these structural constraints, any price decline will be temporary. As soon as demand stabilizes—whether from economic recovery, renewed immigration, or the next interest rate cycle—prices in inelastic cities will resume climbing because supply still cannot respond.

The path forward requires making supply more elastic. Allowing medium-density “missing middle” housing—duplexes, townhomes, low-rise apartments—on land currently restricted to single-family homes would dramatically increase potential supply. This is the single most impactful change cities could make. Reducing regulatory delays and development charges would allow builders to respond more quickly when demand increases, making supply more elastic in the short and medium term. While we can’t move mountains or drain oceans, cities can make better use of constrained land through increased density along transit corridors and near employment centers. Investing in skilled trades training and addressing supply chain issues would increase the speed at which supply can respond to demand signals.

The elasticity framework reveals an uncomfortable truth: Canada’s housing crisis in its major cities isn’t solely a demand problem that will solve itself. It’s a supply elasticity problem that requires deliberate structural reform. Until Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal can respond to demand increases with housing supply rather than just price increases, affordability will remain out of reach for most Canadians.

Paixão, Nuno. 2021. “Canadian Housing Supply Elasticities.” Staff Analytical Note 2021-21. Bank of Canada. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/san2021-21.pdf.